As We May Think: A 1945 Essay on Information Overload, “Curation,” and Open-Access Science:

“There is a new profession of trail blazers, those who find delight in the task of establishing useful trails through the enormous mass of the common record.”

Tim O’Reilly recently admonished that unless we

embrace open access over copyright, we’ll never get science policy right. The sentiment, which I believe applies to

more than science, reminded me of an eloquent 1945

essay by

Vannevar Bush, then-director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, titled

“As We May Think.” As the war, with its exploitation of science and technology, draws to a close, Bush turns a partly concerned, partly hopeful eye to where scientists will rediscover “objectives worthy of their best” and calls for “a new relationship between thinking man and the sum of our knowledge.”

Much of what Bush discusses presages present conversations about information overload, filtering, and our restless “FOMO” — fear of missing out, for anyone who did miss out on the mimetic catchphrase — amidst the incessant influx. Bush worries about the impossibility of ever completely catching up and the unfavorable signal-to-noise ratio:

Professionally our methods of transmitting and reviewing the results of research are generations old and by now are totally inadequate for their purpose. If the aggregate time spent in writing scholarly works and in reading them could be evaluated, the ratio between these amounts of time might well be startling. Those who conscientiously attempt to keep abreast of current thought, even in restricted fields, by close and continuous reading might well shy away from an examination calculated to show how much of the previous month’s efforts could be produced on call. Mendel’s concept of the laws of genetics was lost to the world for a generation because his publication did not reach the few who were capable of grasping and extending it; and this sort of catastrophe is undoubtedly being repeated all about us, as truly significant attainments become lost in the mass of the inconsequential.

More than half a century before blogging, Instagramming, tweeting, and the rest of today’s ever-lowering barriers of entry for publishing content, Bush laments the unmanageable scale of the recorded “human experience”:

The difficulty seems to be, not so much that we publish unduly in view of the extent and variety of present day interests, but rather that publication has been extended far beyond our present ability to make real use of the record. The summation of human experience is being expanded at a prodigious rate, and the means we use for threading through the consequent maze to the momentarily important item is the same as was used in the days of square-rigged ships.

Marveling at the rapid rate of technological progress, which has made possible the increasingly cheap production of increasingly reliable machines, Bush makes an enormously important — and timely — point about the difference between merely compressing information to store it efficiently and actually making use of it in the way of gleaning knowledge. (This, bear in mind, despite the fact that

90% of data in the world today was created in the last two years.)

Assume a linear ratio of 100 for future use. Consider film of the same thickness as paper, although thinner film will certainly be usable. Even under these conditions there would be a total factor of 10,000 between the bulk of the ordinary record on books, and its microfilm replica. The Encyclopoedia Britannica could be reduced to the volume of a matchbox. A library of a million volumes could be compressed into one end of a desk. If the human race has produced since the invention of movable type a total record, in the form of magazines, newspapers, books, tracts, advertising blurbs, correspondence, having a volume corresponding to a billion books, the whole affair, assembled and compressed, could be lugged off in a moving van. Mere compression, of course, is not enough; one needs not only to make and store a record but also be able to consult it, and this aspect of the matter comes later. Even the modern great library is not generally consulted; it is nibbled at by a few.

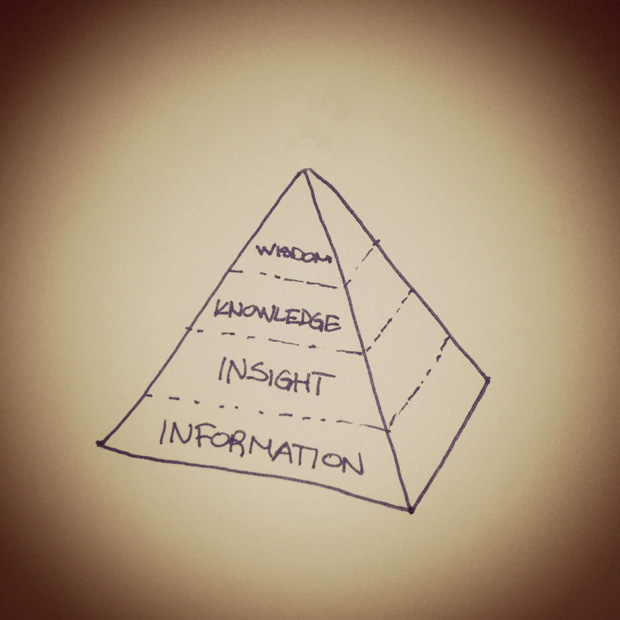

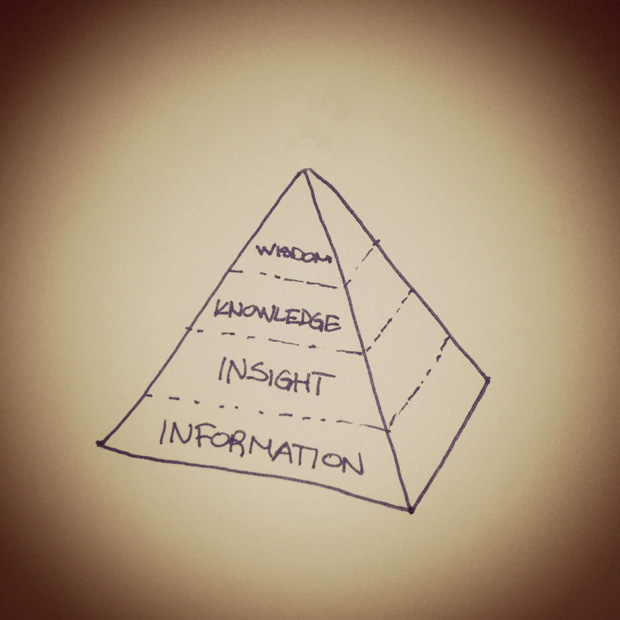

To that end, I often think about the architecture of knowledge as a pyramid of sorts — at the base of it, there is all the

information available to us; from it, we can generate some form of

insight, which we then consolidate into

knowledge; at our most optimal, at the top of the pyramid, we’re then able to glean from that knowledge some sort of

wisdom about the world, and our place in it, and what matters in it and why. Bush himself notes the challenge of transmuting information into wisdom given the scale of what’s available — a scale that has grown by an incomprehensibly enormous magnitude since 1945. He stresses, as many of us believe today, that mechanization — or, algorithms in the contemporary equivalent — will never be a proper substitute just human judgment and creative thought in the filtration process:

Much needs to occur, however, between the collection of data and observations, the extraction of parallel material from the existing record, and the final insertion of new material into the general body of the common record. For mature thought there is no mechanical substitute. But creative thought and essentially repetitive thought are very different things. For the latter there are, and may be, powerful mechanical aids.

[…]

We seem to be worse off than before — for we can enormously extend the record; yet even in its present bulk we can hardly consult it. This is a much larger matter than merely the extraction of data for the purposes of scientific research; it involves the entire process by which man profits by his inheritance of acquired knowledge. The prime action of use is selection, and here we are halting indeed. There may be millions of fine thoughts, and the account of the experience on which they are based, all encased within stone walls of acceptable architectural form; but if the scholar can get at only one a week by diligent search, his syntheses are not likely to keep up with the current scene.

[…]

Selection, in this broad sense, is a stone adze in the hands of a cabinetmaker.

He then gets to the essence of

what we talk about when we talk about “curation”:

The real heart of the matter of selection, however, goes deeper than a lag in the adoption of mechanisms by libraries, or a lack of development of devices for their use. Our ineptitude in getting at the record is largely caused by the artificiality of systems of indexing. When data of any sort are placed in storage, they are filed alphabetically or numerically, and information is found (when it is) by tracing it down from subclass to subclass. It can be in only one place, unless duplicates are used; one has to have rules as to which path will locate it, and the rules are cumbersome. Having found one item, moreover, one has to emerge from the system and re-enter on a new path.

The human mind does not work that way. It operates by association. With one item in its grasp, it snaps instantly to the next that is suggested by the association of thoughts, in accordance with some intricate web of trails carried by the cells of the brain. It has other characteristics, of course; trails that are not frequently followed are prone to fade, items are not fully permanent, memory is transitory. Yet the speed of action, the intricacy of trails, the detail of mental pictures, is awe-inspiring beyond all else in nature.

Man cannot hope fully to duplicate this mental process artificially, but he certainly ought to be able to learn from it. In minor ways he may even improve, for his records have relative permanency. The first idea, however, to be drawn from the analogy concerns selection. Selection by association, rather than indexing, may yet be mechanized. One cannot hope thus to equal the speed and flexibility with which the mind follows an associative trail, but it should be possible to beat the mind decisively in regard to the permanence and clarity of the items resurrected from storage.

The memex

The memex

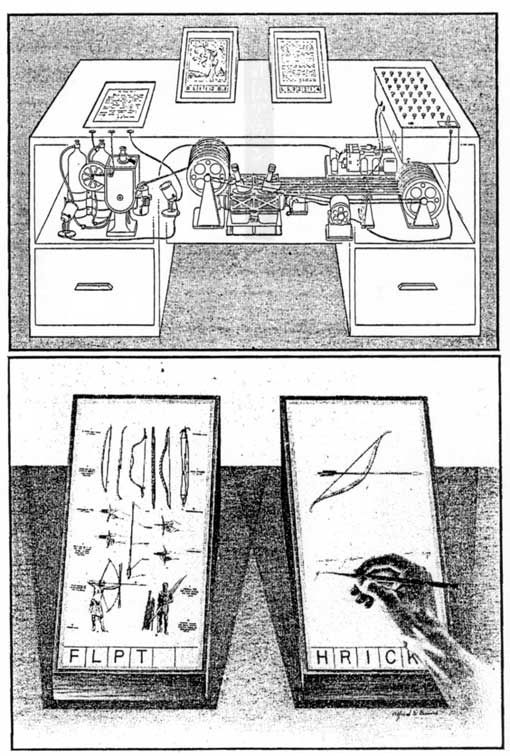

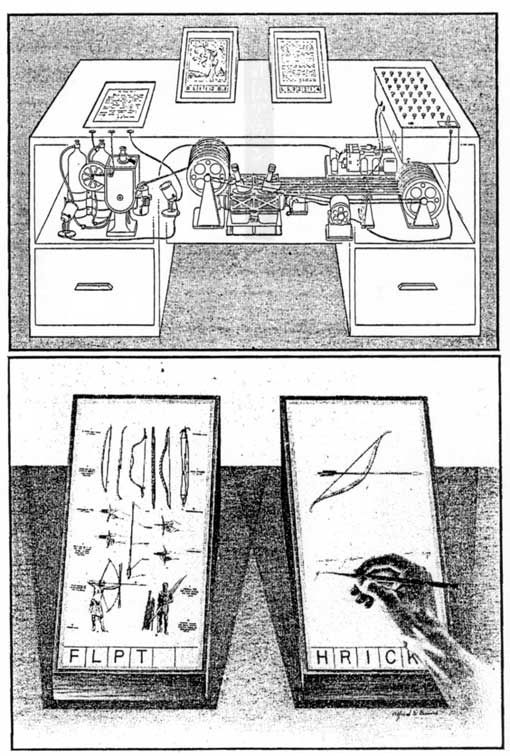

He goes on to envision something called the “memex,” a kind of personal hard drive decades before those became a common way of organizing information, emphasizing the importance of what we now call hyperlinks and metadata — information about the information, often based on associations — in making this personal library navigable and useful:

Consider a future device for individual use, which is a sort of mechanized private file and library. It needs a name, and, to coin one at random, “memex” will do. A memex is a device in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility. It is an enlarged intimate supplement to his memory.

[…]

…associative indexing, the basic idea of which is a provision whereby any item may be caused at will to select immediately and automatically another, [is] the essential feature of the memex. The process of tying two items together is the important thing.

He proceeds to give an example of how the memex would be used, essentially presaging hypertext, the internet, and even Wikipedia — and, perhaps more importantly, laying out a model for what excellence at the intersection of the editorial and curatorial looks like:

The owner of the memex, let us say, is interested in the origin and properties of the bow and arrow. Specifically he is studying why the short Turkish bow was apparently superior to the English long bow in the skirmishes of the Crusades. He has dozens of possibly pertinent books and articles in his memex. First he runs through an encyclopedia, finds an interesting but sketchy article, leaves it projected. Next, in a history, he finds another pertinent item, and ties the two together. Thus he goes, building a trail of many items. Occasionally he inserts a comment of his own, either linking it into the main trail or joining it by a side trail to a particular item. When it becomes evident that the elastic properties of available materials had a great deal to do with the bow, he branches off on a side trail which takes him through textbooks on elasticity and tables of physical constants. He inserts a page of longhand analysis of his own. Thus he builds a trail of his interest through the maze of materials available to him.

And his trails do not fade. Several years later, his talk with a friend turns to the queer ways in which a people resist innovations, even of vital interest. He has an example, in the fact that the outraged Europeans still failed to adopt the Turkish bow. In fact he has a trail on it. A touch brings up the code book. Tapping a few keys projects the head of the trail. A lever runs through it at will, stopping at interesting items, going off on side excursions. It is an interesting trail, pertinent to the discussion. So he sets a reproducer in action, photographs the whole trail out, and passes it to his friend for insertion in his own memex, there to be linked into the more general trail.

Wholly new forms of encyclopedias will appear, ready made with a mesh of associative trails running through them, ready to be dropped into the memex and there amplified. The lawyer has at his touch the associated opinions and decisions of his whole experience, and of the experience of friends and authorities. The patent attorney has on call the millions of issued patents, with familiar trails to every point of his client’s interest. The physician, puzzled by a patient’s reactions, strikes the trail established in studying an earlier similar case, and runs rapidly through analogous case histories, with side references to the classics for the pertinent anatomy and histology. The chemist, struggling with the synthesis of an organic compound, has all the chemical literature before him in his laboratory, with trails following the analogies of compounds, and side trails to their physical and chemical behavior.

Bush nails the value of what we call today,

not without resistance, “information curation”:

There is a new profession of trail blazers, those who find delight in the task of establishing useful trails through the enormous mass of the common record. The inheritance from the master becomes, not only his additions to the world’s record, but for his disciples the entire scaffolding by which they were erected.

He concludes by considering the cultural value and urgency, infinitely timelier today than it was in his day, of making our civilization’s “record” — the great wealth of information about how we got to where we are — manageable, digestible, and useful in our quest for knowledge, wisdom, and growth:

Presumably man’s spirit should be elevated if he can better review his shady past and analyze more completely and objectively his present problems. He has built a civilization so complex that he needs to mechanize his records more fully if he is to push his experiment to its logical conclusion and not merely become bogged down part way there by overtaxing his limited memory.

[…]

The applications of science have built man a well-supplied house, and are teaching him to live healthily therein. They have enabled him to throw masses of people against one another with cruel weapons. They may yet allow him truly to encompass the great record and to grow in the wisdom of race experience. He may perish in conflict before he learns to wield that record for his true good. Yet, in the application of science to the needs and desires of man, it would seem to be a singularly unfortunate stage at which to terminate the process, or to lose hope as to the outcome.

Luckily, for every

Sherry Turkle pushing to “terminate the process” in today’s information society, there’s a

Steven Johnson cheering on its incremental improvement with a fundamental belief in its potential for wisdom and “true good.”

Brain Pickings takes 450+ hours a month to curate and edit across the different platforms, and remains banner-free. If it brings you any joy and inspiration, please consider a modest donation – it lets me know I'm doing something right.

Tim O’Reilly recently admonished that unless we

Tim O’Reilly recently admonished that unless we