Tubes: A Journey to the Center of the Internet:

What undersea cables have to do with Brooklyn squirrels.

Do you ever stop to think what happens when a web page, like this one, manifests as digital text and image on your screen to transmit ideas between someone else’s brain and your own across time and space — and

how it all works, in practical terms? The very thought of this

physical underbelly of our information ecosystem feels strange and uncomfortable, as if betraying our dichotomous culture of “virtual” vs. “real,” cyberspace vs. physical space. And yet, while we may ponder

its cultural impact,

its biases, and

its economics, the internet — despite our metaphors of clouds and information superhighways, and our concept of a “wireless” web — is a thoroughly physical thing. That’s precisely the unsettling realization at which

Andrew Blum arrived after a squirrel in his Brooklyn backyard nibbled through the cable connection of his internet,

the internet, causing it to falter.

Tubes: A Journey to the Center of the Internet records Blum’s quest to uncover what few of consider and even fewer understand — the jarringly tactile, material nuts and bolts of an intricate architectural system we tend to see as an abstract, amorphous blob.

If you have received an email or loaded a web page already today — indeed, if you are receiving and email or loading a web page (or a book) right now — I can guarantee that you are touching these very real places. I can admit that the Internet is a strange landscape, but I insist that it is a landscape nonetheless… For all the breathless talk of the supreme placelessness of our new digital age, when you pull back the curtain, the networks of the Internet are as fixed in real, physical places as any railroad or telephone system ever was.

From the vast data warehouses of major tech companies and giant labyrinths of undersea cables that bridge continents to the nano scale of optical switches and fine fiberglass, Blum reveals an internet that has “a seemingly infinite number of edges, but a shockingly small number of centers.”

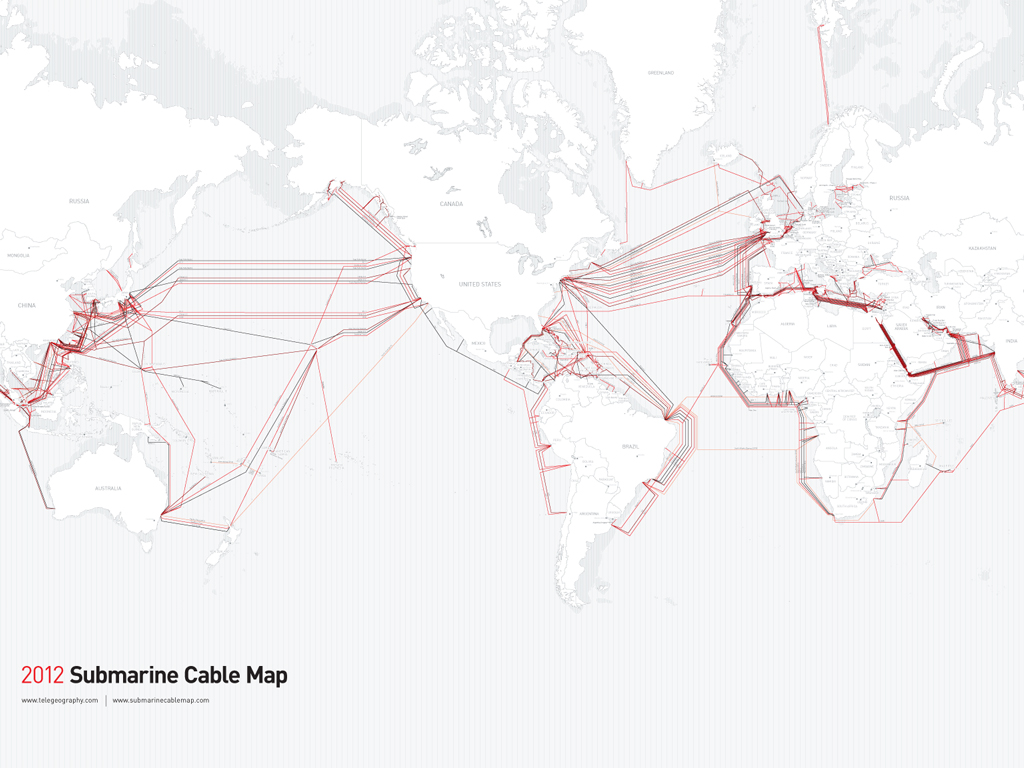

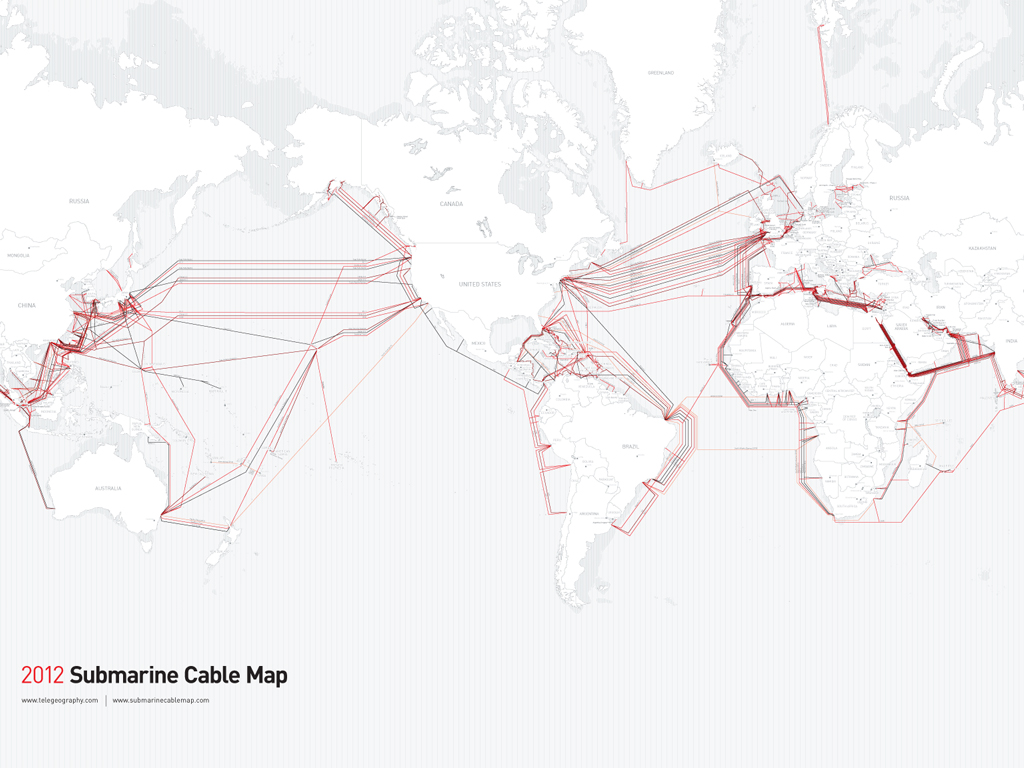

Submarine cable map by TeleGeography, depicting more than 150 cable systems that connect the world.

Submarine cable map by TeleGeography, depicting more than 150 cable systems that connect the world.He writes in the introduction:

This is a book about real places on the map: their sounds and smells, their storied pasts, their physical details, and the people who live there. To stitch together two halves of a broken world — to put the physical and the virtual back in the same place — I’ve stopped looking at web ‘sites’ and ‘addresses’ and instead sought out real sites and addresses, and the humming machines they house. I’ve stepped away from my keyboard, and with it the mirror-world of Google, Wikipedia, and blogs, and boarded planes and trains. I’ve driven on empty stretches of highway and to the edges of continents. In visiting the Internet, I’ve tried to strip away my individual experience of it — as that thing manifest on the screen — to reveal its underlying mass. My search for ‘the Internet’ has therefore been a search for reality, or really a specific breed of reality: the hard truths of geography.

What emerges is Blum’s three-way Venn diagram of understanding:

The networks that compose the Internet could be imagined as existing in three overlapping realms: logically, meaning the magical and (for most of us) opaque way the electronic signals travel; physically, meaning the machines and wires those signals run through; and geographically, meaning the places those signals reach. The logical realm inevitably requires quite a lot of specialized knowledge to get at; most of us leave the that to the coders and engineers. But the second two realms — the physical and geographic — are fully a part of our familiar world. They are accessible to the senses. But they are mostly hidden from view. In fact, trying to see them disturbed the way I imagined the interstices of the physical and electronic world.

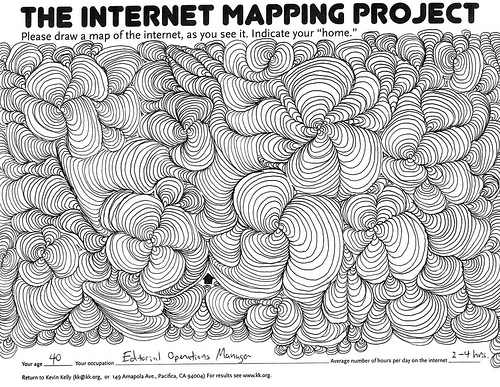

Still, we seem drawn to the spatial and physical mystery of the internet, often visualizing it with the same egocentrism with which medieval man visualized the universe. Blum points to

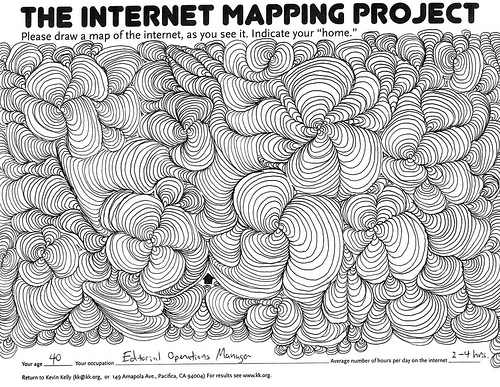

The Internet Mapping Project, in which Kevin Kelly asked ordinary people to sketch how they conceive of the internet, constructing a kind of “folk cartography” and exposing the internet as what Blum calls “a landscape of the mind.”

An entry from Kevin Kelly's Internet Mapping Project, soliciting hand-drawn depictions of the internet.

An entry from Kevin Kelly's Internet Mapping Project, soliciting hand-drawn depictions of the internet.Blum, in fact, dedicates an entire chapter to maps — a treat for a cartographically compulsive

map-lover like myself. In it, he recounts the story of a Milwaukee printer that runs into technical difficulties in printing

TeleGeography’s annual map of the global internet. Blum observes:

The networked world claims to be frictionless — to allow for things to be anywhere. Transferring the map’s electronic file to Milwaukee was as effortless as sending an email. Yet the map itself wasn’t a JPEG, PDF, or scalable Google map, but something fixed and lasting — printed on a synthetic paper called Yupo, updated once a year, sold for $250, packaged in cardboard tubes, and shipped around the world. [This] map of the physical infrastructure of the Internet was itself the physical world. It may have represented the Internet, but inevitably it came from somewhere — specifically, North Eighty-Seventh Street in Milwaukee, a place that knew a little something about how the world was made.

To go in search of the physical Internet was to go in search of the gaps between fluid and fixed. To ask, what could happen anywhere? And, what had to happen here?

But

Tubes is far more than a technical anatomy, revealing instead the broader implications of this seemingly ubiquitous parallel world that two billion of us inhabit, in one for or another, on any given day. In the epilogue, Blum transcends the physicality of his quest to ponder the philosophical:

As everyone from Odysseus on down has pointed out, a journey is really understood upon arriving home. […] What I understood when I arrived home was that the Internet wasn’t a physical world or a virtual world, but a human world. The Internet’s physical infrastructure has many centers, but from a certain vantage point there is really only one: You. Me. The lowercase i. Wherever I am, and wherever you are.

Brain Pickings takes 450+ hours a month to curate and edit across the different platforms, and remains banner-free. If it brings you any joy and inspiration, please consider a modest donation – it lets me know I'm doing something right.

The

The

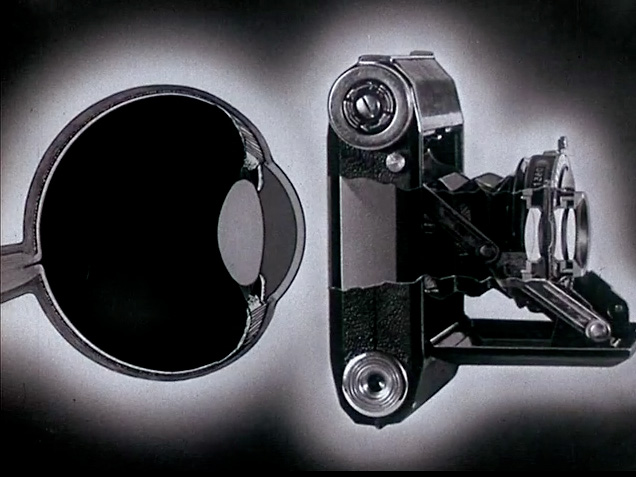

Human vision is one of the most remarkable capacities of our bodies, its precise mechanism the subject of much fascination, from

Human vision is one of the most remarkable capacities of our bodies, its precise mechanism the subject of much fascination, from